Amidst the chaotic crisis of the 3rd century Roman Empire, a breakaway empire emerged in the East. It was ruled by a Warrior Queen. Her name was Zenobia.

Zenobia, born c. 241 CE in Palmyra (modern-day Syria) stands as a pivotal figure in ancient history. She expanded her home-city into an empire from Iraq to Turkey, she conquered Egypt and challenged the fierce dominance of Rome. Her life, marked by leadership, military prowess, and intellectual patronage, is a story of a woman defying gender norms in a male-dominated world. Although her image adorns Syrian banknotes today, the common western ideas of ancient female leaders are largely restricted to Cleopatra, this article aims to bring to light the stunning defiance and fascinating life of the Rebel Queen in the East.

Born as Bat-Zabbai into a powerful family of Palmyra, her early years were marked by culturally defined milestones like menstruation and the transition from childhood to maidenhood which structured the lives of Palmyrene women. These rites of passage, laden with prescribed gender roles, also provided the framework within which Zenobia would later negotiate her identity. Her family life was deeply embedded in the structure of Palmyrene households, where lineage and familial bonds defined social status. Although her roles were circumscribed by patrilineal traditions, the evidence shows that women in her society also exercised considerable influence – through property ownership, benefaction, and even participation in civic life – demonstrating how even within restrictive systems, women like Zenobia found avenues for power.

Zenobia wasn’t just smart—she was dangerously well-educated. Fluent in Aramaic, Greek, Egyptian, and probably Latin, she was raised on philosophy, history, and power. In a world that kept women ornamental, she was sharpening her mind like a blade. And she knew how to use it. This education, likely Hellenistic, included studies of philosophy and history, preparing her for governance. The fact that she was tutored by noted scholars (with links to the intellectual circles of her time) demonstrates the importance placed on learning and self-cultivation. This also illustrates how intellectual resources were available to elite women, revealing the cultural valuation of women’s intellectual capacities.

The future Queen’s transition from maidenhood to marriage was governed by societal expectations. In Palmyra, marriage was viewed as a threshold into full womanhood. As a young woman, she experimented with styles of clothing and personal adornment—public expressions of both gender and status. For instance, her shift from having her hair uncovered as a girl to covering it after marriage reflects broader norms about female modesty and public identity. This negotiation of personal expression within cultural codes reveals both the limits and the creative strategies women employed to assert themselves.

Upon marrying Septimius Odaenathus at age 14 in c.255, a prominent Palmyrene dynast, Zenobia’s biography takes a turn towards the political. Rather than being merely a passive partner, Zenobia’s management of wealth—even seen as exercising “the judgment of a man” by some Roman authors—indicates that she was both shaping and subverting gender expectations. Historical accounts, though debated and complex, document her birth of the pair’s son – Wahballath. However, Odaenathus had one previous son from his first wife: Hairan, who was his presumed heir.

Palmyra, between Syria and Babylonia, was economically dependent upon trade, protecting caravans. Zenobia accompanied her husband, riding ahead of the army, as he expanded Palmyra’s territory, to help protect Rome’s interests and to harry the Persians of the Sassanid empire.

However, accounts suggest after Odaenathus and Hairan were assassinated, Zenobia was left as regent for her son, still only a minor. Some accounts suggest Zenobia herself as a conspirator. Almost immediately, she became the legal guardian and executor of his vast estate. This transition was enabled by local Palmyrene practices that, unlike the strict Roman legal norms, allowed elite women a degree of autonomy over property and household affairs. In doing so, she effectively transformed the dowry and inherited assets into the political and economic foundation for her emerging power.

The death of Odainath occurred during an era of profound instability in the Roman Empire. The 260s were marked by civil strife, frequent usurpations, and external invasions. Claudius Gothicus became Emperor in 268 and was plagued with troubles from the Goths in Thrace (modern Greece). In this volatile context, Zenobia seized her chance and took advantage of Rome’s vulnerability, slowly but surely undermining Palmyra’s once unbreakable bond with Rome.

With her steel-nerved general Zabdas by her side, Zenobia moved fast. Syria fell. Arabia followed. Then Anatolia. Like chess pieces on a burning board, the Eastern provinces flipped allegiance—one after another. Rome, distracted and crumbling, barely noticed. Until it was too late. Ancient sources—though often dismissive or framing her vigour in terms of masculine qualities—reveal that she personally participated in public military ceremonies and assumed leadership roles highly unconventional for a woman of her era.

Zenobia’s reign was not solely defined by military and administrative reforms. Under her rule, Palmyra became a beacon of art, intellect, and cosmopolitan flair. In blending Greek, Roman, and local traditions, Zenobia didn’t just rule an empire—she designed one.

In 269, Zenobia seized Alexandria and a year later had Egypt under her control. When the Roman prefect of Egypt objected to Zenobia’s takeover, Zenobia had him beheaded. This was a great blow to the empire, as Egypt’s grain and wealth were integral. In December 270, coins and papyri were printed in her name as Queen of the East: ‘Zenobia Augusta’. This was a defiant political statement. In aligning her image with the grandeur and legitimacy of the Roman imperial tradition, she boldly asserted her role as a sovereign leader. This self-designation served both as a symbol of her authority and as an ideological tool to strengthen her claim over Palmyra, illustrating how she navigated the male-dominated political landscape of her time with strategic acumen. Zenobia then conquered more lands, in modern-day Syria, Lebanon and Palestine, forging what had now become a true empire – and thus a true threat to Rome.

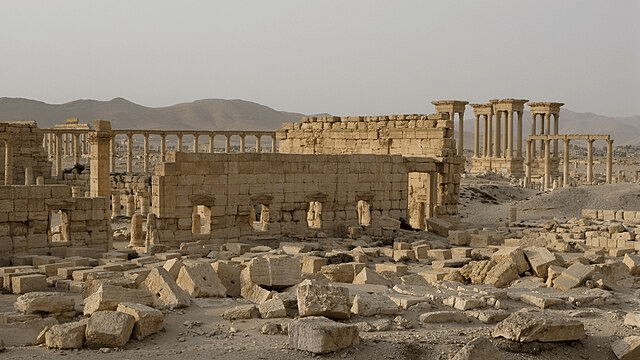

Finally, when Emperor Aurelian turned his attention to the East in his task of reuniting his shattered empire, Zenobia’s forces were eventually pushed back. Near Antioch in Syria, the two armies clashed, and Aurelian’s forces inflexibly overwhelmed Zenobia’s troops. With defeat looming, Zenobia and her son retreated to Emesa in hopes of staging one final stand. However, when the situation grew untenable, she withdrew to Palmyra – a stronghold that soon fell to Aurelian’s advancing legions. In a desperate bid for escape, she fled on a camel, attempting to secure refuge with the Persians, but was eventually captured by Aurelian’s troops along the Euphrates. Aurelian ordered the execution of those Palmyrans who refused to surrender. The city of Palmyra itself was largely destroyed and rebuilt again, serving as an important regional city under the Byzantines. Zenobia’s fate remains debated: some sources suggest she was paraded in Aurelian’s 274 AD triumph, others claim she starved herself or lived in a villa near Rome.

A letter from Aurelius reads: “Those who speak with contempt of the war I am waging against a woman, are ignorant both of the character and power of Zenobia. It is impossible to enumerate her warlike preparations of stones, of arrows, and of every species of missile weapons and military engines.”

Zenobia’s legacy is of utmost significance. Since her death she has been hailed as an ambitious and courageous role model, especially in the Middle East, standing alongside contemporaries like Cleopatra and Boudicca. Most notably in 19th century Syria she became a nationalist icon, her image representing the immense power once held by the region.

In 2015, the ancient city of Palmyra suffered devastating destruction at the hands of ISIS militants. The terrorists systematically dismantled much of the site’s irreplaceable monuments and cultural treasures, including temples, arches, and sculptures, as part of their ideological campaign to erase pre-Islamic history and cultural diversity. This ruthless campaign not only represented a tragic loss to world heritage but also served as a stark reminder of the vulnerability of cultural sites in conflict zones.

Queen Zenobia’s life illustrates the tension between societal constraints and personal agency. Ancient sources, like the infamously dodgy Historia Augusta and inscriptions from Palmyra, often employ masculine language to describe her actions, emphasizing that her effective governance and generous benefactions were “manly” in nature. But her actions were expressions of autonomous power, reflecting a sophisticated approach to leadership that transcended binary gender expectations. Her administration, military exploits, and cultural patronage collectively underscore a legacy of resilience and visionary rule – a legacy that challenges simplistic narratives of gender in antiquity and continues to inspire discussions about female leadership and autonomy.

Zenobia’s rebellion may have failed militarily, but it succeeded in writing her into history—not just as a warrior queen, but as an icon of resistance, resilience, and Renaissance vision long before her time.

Her incredible story isn’t just an ancient biography—it’s a masterclass in defiance. She broke the rules, bent empires, and rewrote what power could look like. Described as “manly” by ancient authors, it is clear that she scared them. She was everything they thought a woman couldn’t be—strategic, commanding, relentless. And that, more than anything, is why she still matters profoundly.