“Let no-one escape sheer destruction, no-one our hands, not even the babe in the womb of the mother, if it be male; let it nevertheless not escape sheer destruction.”

These were the alleged bloodthirsty words which emperor Septimius Severus barked to his Roman soldiers in the 3rd century as they marched towards the looming Caledonian hills shrouded in fog. A force of over 40,000 soldiers was attempting to push the northerly frontier of the empire further than ever before – into Scotland. A ‘war of extermination’ was unfolding, where natives were slaughtered by the thousands and villages were burned to the ground, in a bloody affair some today call genocide. A severe illness caused the emperor’s untimely death in 211, thus bringing an end to his Caledonian ambitions. Let’s explore Severus’ story and attempt to understand why this North-African born emperor spent his final years trying to conquer the unconquerable.

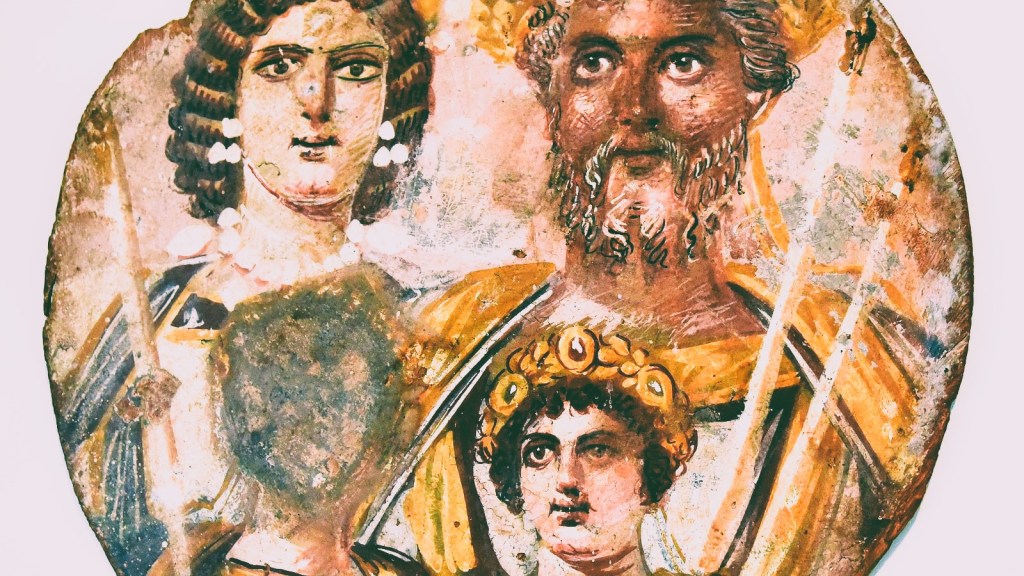

Born in Leptis Magna (modern Libya) to a wealthy family, young Severus demonstrated signs of ambition from a young age, seeking a public career in Rome by 162. And with the recommendation of his relative, emperor Marcus Aurelius granted him entry into the illustrious senatorial class. However, in the following years under Commodus, Severus faced several issues as a politician. As a provincial, he likely faced prejudice and was viewed as an outsider by many senators from Italy or traditional noble lineages. Yet Severus was no fool—he kept his head down, played the long game, and steadily climbed the ranks, gaining vital administrative and military experience while avoiding the deadly court politics that consumed so many of his peers. Governorships in Gallia Lugdunensis and Syria showcased his competence, while his African roots and connections helped him build a loyal base beyond Rome’s inner circle. When Commodus’ erratic rule ended in chaos and the empire spiralled into civil war after the assassination of Pertinax in 193, Severus seized the moment. Backed by the powerful legions of the Danube, he marched on Rome, ousted the puppet emperor Didius Julianus, and was declared emperor—an outsider no more, but the new master of the Roman world.

Severus’ rise held particular significance from an African perspective. As the first Roman emperor born in Africa, his ascent challenged the deeply ingrained Italic elitism of the Roman aristocracy. For many across North Africa, Severus symbolised the possibility of imperial power being shaped not just in Rome, but on the empire’s periphery. His African heritage wasn’t merely a footnote; it was central to his identity, and he later invested heavily in Leptis Magna, turning it into a monument to his legacy and a visible reminder that emperors could rise from the margins.

By the early 200s, Severus was an ageing emperor with a sharp mind, a ruthless streak, and something to prove. Though his rule had brought stability after civil war, he was increasingly preoccupied with legacy—how he would be remembered. Britain, restless and divided, offered the perfect stage. Revolts had broken out north of Hadrian’s Wall, and the Caledonian tribes remained defiantly unconquered. No Roman emperor had ever managed to bring the far north under lasting control, and Severus saw an opportunity to do what even Hadrian and Antoninus could not: crush resistance, redraw the frontier, and immortalise himself as the conqueror of Caledonia. So, in 208, he left the comfort of Rome and travelled to Britain with his sons, Caracalla and Geta, preparing to wage what would become the bloodiest and most brutal campaign of his reign.

Severus landed in Britain with over 40,000 of the toughest, fully equipped Roman soldiers. Alongside him were his two sons, Caracalla and Geta—dragged into the far north not only to witness Roman warfare firsthand, but to prove themselves as heirs. But this was no swift nor easy conquest. The Caledonian tribes, fragmented yet fierce, refused to meet the Romans in open battle. Instead, they waged a relentless guerrilla war, striking from the hills and vanishing into the wilderness. The Scottish terrain had the natives’ back: bogs, mountains, dense forests—all slowed the Roman advance. Progress was agonisingly slow, and casualties mounted, not just from ambushes but from disease, hunger, and exhaustion. In response, Severus turned to scorched-earth tactics. Villages were razed, crops destroyed, and livestock seized. The message was clear: annihilation over assimilation. The goal wasn’t just victory; it was to break the will of the Caledonians entirely. Tensions simmered between the brothers during the campaign, and Severus, already unwell, reportedly grew frustrated with their rivalry and lack of discipline. Yet despite the cruelty and cost, Severus couldn’t claim his full success.

The land refused to yield, and resistance persisted. As his health declined, he withdrew to Eboracum (modern York), where he watched from a distance as Caracalla continued the campaign. Geta, meanwhile, was left out of military command altogether, isolated in court and sidelined by his elder brother. The friction between the brothers during the campaign foreshadowed the deadly rift to come—just a year later, Caracalla would have Geta murdered, turning their father’s final war into a prelude for fratricide. In 211, before any decisive outcome, Severus died—worn down by illness, war, and a landscape that refused to be conquered. His campaign ended as it began: ambitious, savage, and ultimately unresolved. Caledonia remained wild, unconquered, and free.

Severus’ death in Eboracum marked the end of Rome’s last serious push into Scotland. Caracalla, now in full command, abandoned the campaign and withdrew behind Hadrian’s Wall, cutting losses and securing a fragile peace. The invasion had cost thousands of lives, drained imperial resources, and delivered no lasting gains. Yet the war revealed the limits of Roman power at the empire’s edge, and it underscored Severus’ obsession with legacy and control. In death, he left behind not a conquered land, but a transformed empire—one more dependent on military force, less on senatorial tradition, and permanently shaped by the ambition of a provincial outsider who had clawed his way to the top.

So was this Rome’s last gasp in the north? A final roar from an ageing emperor desperate to etch his name into history—or a futile gesture against a land that was never his to take? Severus has been remembered as both a visionary and a madman: a man who stabilised an empire torn apart by civil war, but who wasted his final years chasing a fantasy of total conquest. His words—“Let no one escape sheer destruction…”—now echo less as a battle cry and more as a warning. For all his might, all his legions, and all his ruthless resolve, he died short of his goal, defeated not by men, but by mud, mist, and the sheer will of an unconquered people.

In the end, the campaign stands as a monument not to Roman power, but to its limits. Empires stretch, empires break—and even the most iron-willed emperors can be undone by the ground beneath their feet.