The field of archaeology is overwhelmingly whitewashed. From lecture halls to dig sites to documentaries, I rarely see a non-white face. The past, present, and future of archaeology is stubbornly white.

In the United Kingdom, a 2020 survey found that 97% of professional archaeologists identified as white. Historic data shows that the percentage increased from 99% in 2002 to 99.2% in 2013 — despite the UK population becoming significantly more diverse during that period.

In the United States, a 1994 survey by the Society for American Archaeology found that 98% of respondents identified as of European heritage, with just 2% identifying as non-white. By 2011, things had only marginally improved, with white archaeologists still making up around 84% of the field — a slow pace of change that exposes systemic barriers to entry and retention.

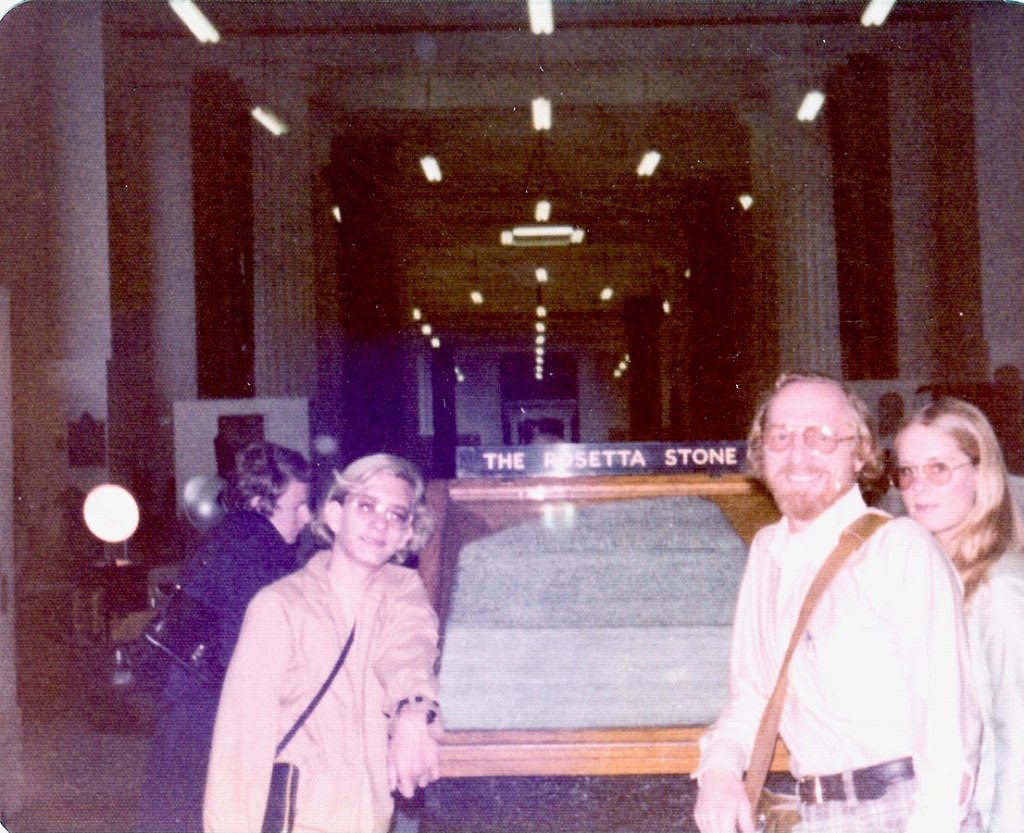

But whiteness in archaeology isn’t just about who’s doing the digging — it’s also about which histories are told, and how. Archaeology remains gripped by a Eurocentric worldview. I’m tired of hearing about Europe. My lectures are dominated by European examples: Greece and Rome are fascinating, but they should not be elevated to the pinnacle of civilisation as if nothing else compares. Asia, Africa and the Americas are neglected time and time again. Even when they are discussed, it’s often by white archaeologists, through white institutions, and from a Western perspective. The reason for such Eurocentrism lies at the dark heart of archaeology – colonialism. Europeans just love to claim foreign lands as their own and when they do, they like find treasures which clearly belong to them.

To understand why archaeology is so white, you must look at where it started — and it wasn’t in some neutral, noble quest for knowledge. It was born in the age of empire, shoulder to shoulder with colonial expansion. When Europeans went sailing around the globe planting flags and stealing land, they also started digging. Not to preserve the past, but to possess it.

This was the era of adventure archaeology — diabolical taches, goofy helmets, and rather sketchy claims to artefacts. Men like Flinders Petrie in Egypt, or Heinrich Schliemann digging up Troy, weren’t just chasing history. They were writing themselves into it, turning excavation into ego, empire into science. Of course they were white, rich, and male — because the institutions that trained and celebrated them were built for exactly that kind of person. Museums became treasure vaults, filled not with donations but with straight plunder.

Today, I believe the whiteness of archaeology still stains the field. Think about media: Indiana Jones, Time Team, National Geographic—all dominated by white faces shooting into tombs or dusting off classical gems. The stereotype undoubtedly turns people away who don’t fit the mould.

The reality is fieldwork and academic entry are still blocked by barriers rooted in race and class. Field schools often cost thousands—tuition, travel, lost summer wages—and even tiny scholarships barely scratch the surface. Finding paid internships or jobs is just as hard—especially if you can’t drive, don’t have network connections, or have caregiving responsibilities.

There are other ways to do archaeology—ways that centre the people whose ancestors lived on the land being studied. Community archaeology offers that hope: locals leading the work, owning the story. But even then, those projects are rare, and still often led by white Europeans, parachuting in with funding and frameworks that don’t always translate.

And this isn’t just about box-ticking diversity. In archaeology, who gets to ask the questions determines which pasts are remembered. If only one kind of person chooses what’s worth excavating, interpreting, and preserving, then whole histories get left in the dirt. The field suffers. The story of humanity gets thinner. The past becomes a mirror, reflecting only the people already holding the torch.

Still, there are signs of shifts which should be recognised. Scholars like Dr. Ayana Omilade Flewellen and Dr. Alexandra Jones are leading the way, carving space for Black voices in a field that so often silences them. Community-led projects across the Caribbean, Africa, and Indigenous North America are reclaiming the narrative, doing archaeology with people, not just on their land. And students everywhere are demanding change: more inclusive curricula, more global perspectives, fewer dead white men at the centre. I’m proud be part of this wave —opening up archaeology, telling richer stories, and helping build a field where more people feel like they belong.

But let’s not pretend the establishment is racing to change. Britain still clings to its colonial pride like a museum label that hasn’t been updated in decades. Elites sit on ivory towers and parliamentary benches, preaching heritage while still refusing to return the stolen artefacts. The British Museum is a trophy cabinet of imperial conquest, yet government officials call repatriation revisionist or woke. They’ll spend millions preserving crumbling abbeys but barely invest in making archaeology more accessible, inclusive, or just. For a country so obsessed with the past, Britain still refuses to face its own.

If we want archaeology to evolve, we have to change the foundations it stands on. That starts with money—funding needs to be made available for underrepresented students, not just the ones who can afford to pay their way into a trench because they can’t decide what else to do with their life. Fieldwork, internships, and travel should be accessible, not a luxury. We need to bring descendant communities to the centre—not as tokens or afterthoughts, but as partners, decision-makers, storytellers. The curriculum must be torn open too. Less worship of Western “greatness,” more global, more honest. And the whole model of excavation needs flipping—from extraction to collaboration, from ownership to stewardship. Finally, we must expand the image of who gets to be an archaeologist. Not just the tweed-jacketed academic or the sunburnt white boy—but everyone. Curious kids from Brixton, elders in Oaxaca, young women in Nairobi, queer students in Glasgow. Together. That’s the future.

Archaeology is about digging up the past—but now it’s time to dig deeper into the discipline itself. If we want to tell fuller, richer human stories, we need more voices in the room and more hands in the soil. The past belongs to all of us—so let’s stop letting only a few people hold the spade.

Sources:

2.6 Ethnicities of Archaeologists – Profiling the Profession